Love Island star Georgia Steel on the impact of trolling: ‘I felt like everyone hated me – it made me feel like I didn’t know myself’ | Ents & Arts News

“Hate and death threats and abuse, and personal, deep things. All the hate out there… I don’t think anyone can prepare you for that.”

Georgia Steel doesn’t find it easy talking about the trolling directed at her during her time on Love Island, but says it is an issue she needs to address.

The reality star rose to fame in 2018, when, aged 20, she appeared in the fourth series and earned her place among the show’s most memorable contestants.

In January this year, with more than 1.6m followers on Instagram, TikTok and other platforms, she returned to appear in a new “all stars” version of the show in South Africa.

She found herself at the centre of the drama after – shock! – flirting with someone who wasn’t her “partner” at the time, and eventually getting together with a different contestant, Toby Aromolaran, after he unceremoniously ditched the partner he was with without warning during a public recoupling, and declared his interest in Steel. (They left the show together, but she revealed last week he had called things off).

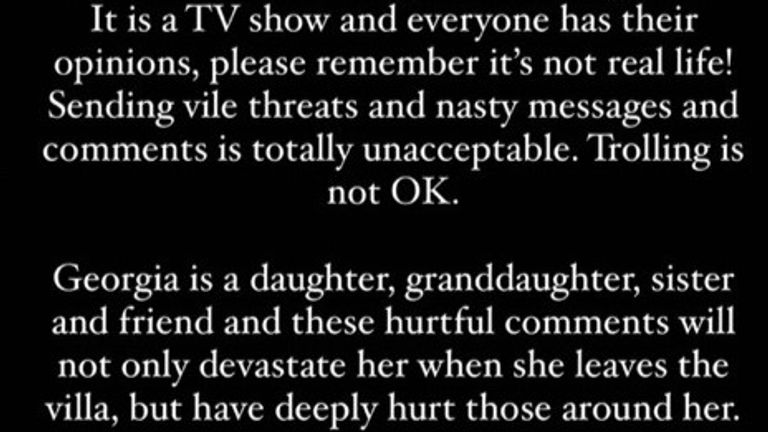

This is essentially the extent of her crimes. The reaction was so vicious that her family and management team, looking after her social media accounts while she was cut off from the real world, decided to step in, sharing this post.

To the uninitiated, the romances and fall-outs of 20-somethings who have spent a maximum of five weeks together might seem trivial, but viewers become invested. “It’s a reality show, it’s not real life,” Steel points out. “You’re not in a normal situation.”

Steel comes across as a confident, funny, glamorous young woman on TV. In person, she is still all of those things, but more fragile.

Most of the hundreds of messages were deleted before she was reunited with her phone to save her from the extent of the cruelty, and she becomes tearful hearing the words her loved ones felt were necessary to make public.

“For the people I love to have witnessed those things, it is terrible, awful, and it does make me feel slightly responsible.”

‘A tidal wave of abuse’

Online trolling has been a rising problem for years and one that doesn’t appear to be going away.

Anyone sending serious violent threats faces up to five years in prison – but despite the calls to “be kind”, the stories of abuse continue – as seen in recent weeks towards previous Love Island winner Ekin-Su Culculoglu following her time in the revived Celebrity Big Brother.

Then there was the trolling of Amber Heard during the Johnny Depp court cases, now the subject of a new investigative podcast.

Most recently, the world has been given a grim reminder of the potential effects of online gossip and trolling following the Princess of Wales’s public announcement of her cancer diagnosis.

Anti-bullying and online abuse charities and organisations say the majority of trolling is directed at women, and Ofcom research in 2022 found that 60% of women were concerned by the issue, compared with 25% of men.

Read more:

Amy Hart: ‘Cyber flashers’ bombard me with penis photos

How did online abuse of Amber Heard become acceptable?

Georgia Harrison on her fight against revenge porn

Research by the Center for Countering Digital Hate into the direct (private) Instagram messages of five prominent women, including Heard and Countdown’s Rachel Riley, found that around one in seven were abusive, either through misogynist comments or sending unsolicited sexual advances.

Founder and chief executive Imran Ahmed says it can be “traumatising to receive a tidal wave of abuse”, and that he has known “strong, empowered people who found themselves in a heap on their sofa, crying, because that’s just what it’s like to have thousands of people screaming swear words at you”.

Linda James, founder and chief executive of the BulliesOut charity, says trolling can be “relentless and dangerous”, and that “even the nicest, most reasonable, and mild-mannered people in real life” can exhibit trolling behaviour once they are online.

‘You don’t know if the whole world hates you’

Most of the direct abuse sent to Steel, who celebrated her 26th birthday earlier this week, came through Instagram, but there were other “horrible” posts on TikTok and shared on Facebook and X (formerly Twitter), her team said.

Steel is aware that being in the public eye means strangers will have opinions of her – but says there is a difference between opinion and threats and bullying.

“You don’t really know how to process it… you’re quite scared,” she says. “You don’t know if the whole world hates you – I felt like everyone hated me.”

The worst thing was knowing her family and friends had also been sent abuse, that they had seen the comments written about her. “It made me question everything I did,” she says.

“It made me feel like I didn’t know myself to a certain degree… My family, my friends, they had death threats. My mum got messages like, ‘How could you raise a girl like this?’ I just want to make the people that support and love me proud. I know that they still are. But it makes me worry that they’re not.”

For an influencer whose career revolves around social media, it has been a tricky balancing act trying to keep away from it all. But after finishing the show and getting her phone back, she turned it off and left it for a week.

“I needed to rebuild my confidence,” she says. “I spent it with my mum and my dad and my brother, and I just wanted reassurance constantly. ‘Have I done anything wrong? What could I have done better?'”

It’s sad to hear Steel say she accepts that to many viewers, she was the “villain” of this latest season of Love Island.

She is, after all, a young woman who flirted and had her head turned, to use the Love Island lexicon – on a reality show that survives on flirting and contestants having their heads turned. She says Aromolaran did not receive the same level of abuse.

“I am still a person. I’m a [young] girl, I’m still learning my way. I’m not perfect. If anything, me making mistakes on a show, it shows that I’m genuine and that I’m real. But instead, it was kind of used against me… is it because I’m a woman? Is it double standards? I don’t know.”

The anonymity is one of the hardest things to come to terms with. She said: “It’s like going into a shop and wearing a balaclava and abusing someone… these people are hiding behind anonymous names and fake accounts.

“There’s definitely times when I’d be out and thinking, they’re looking at me… ‘Oh my God, is that one of the trolls?’ It makes it really scary because you just don’t know who they are.”

Steel says she does not blame ITV or Love Island for the trolling as they cannot control what people say online, and that support from the show’s producers “is always there if you need it”.

When the trolling against the star was announced, producers put out a statement urging viewers “to be kind when engaging in social media conversations about our Islanders, and to remember that they are real people with feelings”.

Trolling ‘bleeds over’ into real world

In recent years, the broadcaster has announced greater duty of care protocols for its reality show participants and last year implemented a ban on Love Island contestants’ social media accounts being active during their time on the show – although All Stars participants, as they already had public profiles, were given the option.

Steel thinks social media platforms should be doing more, and that the solution is simple.

“It would just be literally having an ID when you sign up to an account or having some proof of who you are, instead of constantly going behind a screen and being anonymous. That’s what I really don’t understand. I don’t understand how that’s allowed, if I’m honest.”

In its information on anti-bullying features and tools, Instagram says it is committed to protecting users and urges people to report anything that violates its guidelines so that action can be taken if necessary, while TikTok says it does not “allow language or behavior that harasses, humiliates, threatens, or doxxes anyone”.

X says it prohibits “behaviour and content that harasses, shames, or degrades others”, while Facebook also says it does not “tolerate this kind of behaviour because it prevents people from feeling safe and respected”.

Read more:

What is the Online Safety Act?

Alex George: Grief can destroy you – but can be a force for good

Last year, the Online Safety Act was passed by MPs, requiring providers of online services to minimise the extent of illegal and harmful content.

Once implemented, the act will require social media firms to enforce “stringent measures against criminal online abuse”, a government spokesperson said, including “proactively tackling exposure to illegal content that can disproportionately affect women and girls, including controlling and abusive behaviour”.

Before this can be enforced, new codes of practice and guidance have to be produced.

A spokesperson for Ofcom told Sky News these are expected to be finalised around the end of the year, while further proposed measures “to protect children from sexist hate and abuse specifically” will be announced in May.

The Center for Countering Digital Hate says things need to change, and that online trolling and division can have real-world consequences.

“We have to stop this epidemic of abuse,” Mr Ahmed says. “It starts to bleed over and resocialise our real world as well, which is why we can see that relations in our society, our politics, our discourse are becoming more fragmented, more vicious, less productive and less conducive to the kind of democracy we want.”

‘That one comment could tip someone over the edge’

Steel says she wants to speak out as she feels she is in a position where she is able to, with an “amazing” support system in her friends and family at home in York.

“I’m very lucky,” she says. “I want to admit: I got trolled really, really, really bad. And yeah, it really, really, really affected me. But I am okay. And some people, if they were in my position, might not be okay.

“I think some people are built stronger than others or some people have better foundations than others, and the ones that maybe don’t, they’re the ones that we really have to think about.”

Two former Love Island contestants, Sophie Gradon and Mike Thalassitis, have ended their own lives. Gradon died in 2018, two years after appearing on the show; Thalassitis the following year, also two years after taking part.

Gradon had reportedly spoken about the “horrific” trolling she experienced in a radio interview in the months before her death, while Montana Brown, a contestant in Thalassitis’s season, urged people to “be a little bit nicer, little bit kinder“, following the inquest into his death.

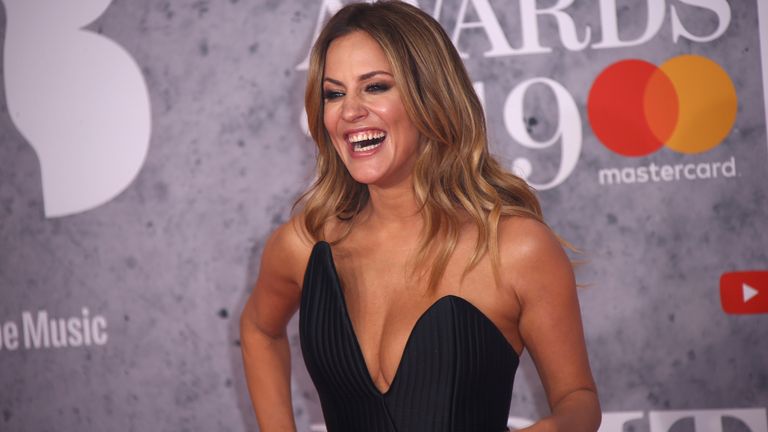

It was the suicide of Love Island presenter Caroline Flack in 2020 that sparked the “be kind” encouragement on social media. But Steel isn’t convinced people are taking notice.

“Caroline presented my show in 2018 and I never expected that to happen,” she says. “As much as we talk about it and say it’s not okay, I think there actually needs to be something set in place, before it’s too late and something else happens, and then it’s just a vicious circle. It’s, ‘we’ll be kind for a bit, and then we’ll forget about it, and then someone else… then we’ll be kind for a bit again’. That circle needs to stop.”

She wants people to know how much abuse can hurt.

“I feel like maybe some [trolls] really want to see me down, which… I am. So you’ve won. But I will also prove a point that trolling can’t be allowed.”

Finally, she says she wants social media users to really, really think hard about anything they have written before pressing send.

“Would you say this to them if they were sat across the table? Would you say things to their family and their friends? Would you be happy if the consequences were really bad?

“It could just take that one comment that tips someone over the edge. Would you want to be accountable for that?”

Anyone feeling emotionally distressed or suicidal can call Samaritans for help on 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.org in the UK. In the US, call the Samaritans branch in your area or 1 (800) 273-TALK